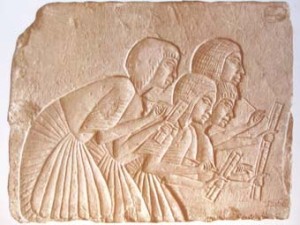

Talking goes on quite a while before writing – in history as well as personally. For a million years we just had talking, 50,000 languages or so. Around 1500 B.C.E., writing became a human tool, but talking still remains primary. Literature since then has developed in only about 100 languages. Even today, with roughly 3000 spoken, only 80 or so have literature.

Talking goes on quite a while before writing – in history as well as personally. For a million years we just had talking, 50,000 languages or so. Around 1500 B.C.E., writing became a human tool, but talking still remains primary. Literature since then has developed in only about 100 languages. Even today, with roughly 3000 spoken, only 80 or so have literature.

Talking comes naturally; writing doesn’t. We’re born making sounds, not jotting notes. The first words, across all cultures are “Mm” and “ah” sounds for Ma, and plosives like “d” and “p” for Pa. But from there the universality of language peters out to “huh,” and you begin learning the unique sounds your society assigns to things and actions. After, say, a year, you begin to speak the mother tongue of your fatherland.

Speech distills a mash of thought into coherence. It filters a pertinent essence from all you’re thinking. You may have heard it said, “I don’t know what I mean until I say it.” Talking exercises your meaning-filter, and exercise strengthens and builds up. It’s hard to overestimate how essential this filter is to the nature and quality of our lives. It’s the same filter your brain applies to the sense and abstract data constantly flooding every heartbeat of your life. It’s also the filter that prompts your attention, and your attention is what writes your life story! So training that filter is key to living in a way you like.

Numerous matters contribute to the state of your filter: pain and reward, for example, and what fascinates you. Talking is a star player in this processing game, but writing jumps you to the big leagues. It filters the filtering to an nth degree. As Einstein famously said, “My pencil and I are smarter than I am.” Einstein is the talker, and the pencil is writing.

“I don’t know what I mean until I say it” translates for a writer as: “I don’t know what I’ve written until I’ve edited it.” Writing lets you rewrite and rewrite until you can’t think of a better way to say it. T.S. Eliot did this very thing to nail his description of good writing (fair to say, it practices what it preaches):

…where every word is at home,

Taking its place to support the others,

The word neither diffident nor ostentatious,

An easy commerce of the old and the new,

The common word exact without vulgarity,

The formal word precise but not pedantic,

The complete consort dancing together.

— (from the end of “Little Gidding”)

Talking aims to distill thought to shared meaning; writing takes pains to perfect that aim. Writing distills from talking everything that isn’t thought, everything extramental. It aims for the purest meaning that words can say. In our search for meaning, writing is a prime power tool.

Despite the savagery and dominant sway of stupidity in the world today, a good case can be made that human consciousness has evolved over the eons. It’s maybe easier to see how as individuals, our consciousness has similarly evolved from birth to our current state of understanding. Literacy has been a huge jumpstarter for both types of evolution.

All sorts of advancements occur once literacy hits a culture, from technology to democracy. Literacy enables technological knowledge to spread and grow – the wheel no longer has to keep being re-invented. Literacy also democratizes: more and more people have access to knowledge that used to be privileged.

Big changes also happen personally once we learn to read and write, changes even more sweeping than when we learn to stand, walk and run. Talking expands our reach beyond our physical reach, and writing expands our range far beyond that of the human voice. Literacy doesn’t necessarily make a person good, but literacy does open up our lives. It helps us get more out of life, sharpens and extends consciousness, and helps you spend more quality time with your mind. There’s a reason beyond social embarrassment that illiteracy is regretful. Those who can’t read or write know they’re missing out on a much wider world.

Writing that tries to get just the right words shapes up our filter like nothing else. Editing – rewriting and rewriting – is a paradigm way of getting at truth, ever-elusive but more important at the end of the day than death or taxes. If we want to better our lives, we have to edit them.

Our story isn’t written yet. We write it as we go along, and good writing means rewriting until we get it right. If we don’t edit, we remain stuck in an unevolving mindset. Good literature pulls us out of literalism like Arthur pulled Excalibur from the rock. It doesn’t say “This is the answer, go no further.” It says, “The letter kills; the spirit gives life.”

Our story isn’t written yet. We write it as we go along, and good writing means rewriting until we get it right. If we don’t edit, we remain stuck in an unevolving mindset. Good literature pulls us out of literalism like Arthur pulled Excalibur from the rock. It doesn’t say “This is the answer, go no further.” It says, “The letter kills; the spirit gives life.”

If pride and mental smugness close our minds to editing, we give up on vibrant life and its ever-unfolding disclosures. The honest work of writing well, expressing yourself as best you can, improves your ability to seek – and the quality of what you shall find.